what did Wollstonecraft argue that men must do if they want to prove women are inferior

| |

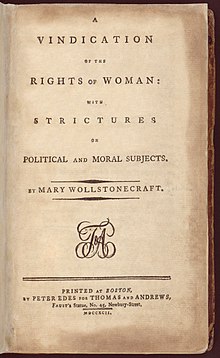

| Author | Mary Wollstonecraft |

|---|---|

| State | United kingdom |

| Linguistic communication | English language |

| Subject | Women'southward rights |

| Genre | Political philosophy |

| Publication date | 1792 |

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (1792), written past the 18th-century British proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, is 1 of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft responds to those educational and political theorists of the 18th century who believed that women should non receive a rational teaching. She argues that women'south education ought to match their position in society, and that they are essential to the nation considering they raise the children and could deed equally respected "companions" to their husbands. Wollstonecraft maintains that women are human beings deserving of the same cardinal rights as men, and that treating them equally mere ornaments or property for men undercuts the moral foundation of society.

Wollstonecraft was prompted to write the Rights of Woman after reading Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord'south 1791 report to the French National Assembly, which stated that women should simply receive a domestic instruction; from her reaction to this specific upshot, she launched a broad assail against sexual double standards, indicting men for encouraging women to indulge in excessive emotion. Wollstonecraft hurried to complete the work in straight response to ongoing events; she intended to write a more thoughtful second volume but died earlier completing it.

While Wollstonecraft does call for equality between the sexes in item areas of life, especially morality, she does not explicitly state that men and women are equal. Her cryptic statements regarding the equality of the sexes have made it difficult to classify Wollstonecraft as a modern feminist; the word itself did non sally until decades after her expiry.

Although it is commonly assumed that the Rights of Woman was unfavourably received, this is a modern misconception based on the belief that Wollstonecraft was as reviled during her lifetime equally she became afterward the publication of William Godwin's Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798). The Rights of Woman was generally received well when it was first published in 1792. Biographer Emily W. Sunstein called it "perhaps the most original book of [Wollstonecraft'south] century".[ane] Wollstonecraft's work had significant impact on advocates for women's rights in the 19th century, particularly the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention which produced the Annunciation of Sentiments laying out the aims of the suffragette movement in the United States.

Historical context [edit]

A Vindication of the Rights of Adult female was written against the tumultuous background of the French Revolution and the debates that it spawned in Great britain. In a lively and sometimes cruel pamphlet state of war, now referred to every bit the Revolution controversy, British political commentators addressed topics ranging from representative government to human rights to the separation of church and land, many of these issues having been raised in France first. Wollstonecraft first entered this fray in 1790 with A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a response to Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in French republic (1790).[2] In his Reflections, Burke criticized the view of many British thinkers and writers who had welcomed the early stages of the French revolution. While they saw the revolution as coordinating to U.k.'s own Glorious Revolution in 1688, which had restricted the powers of the monarchy, Burke argued that the appropriate historical analogy was the English language Civil War (1642–1651) in which Charles I had been executed in 1649. He viewed the French revolution equally the tearing overthrow of a legitimate regime. In Reflections he argues that citizens do not have the right to revolt against their government because civilization is the event of social and political consensus; its traditions cannot be continually challenged—the result would be anarchy. 1 of the key arguments of Wollstonecraft's Rights of Men, published just six weeks after Burke'southward Reflections, is that rights cannot be based on tradition; rights, she argues, should be conferred considering they are reasonable and only, regardless of their basis in tradition.[3]

When Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord presented his Rapport sur fifty'instruction publique (1791) to the National Assembly in France, Wollstonecraft was galvanized to reply.[4] In his recommendations for a national arrangement of education, Talleyrand had written:[5]

Allow us bring up women, not to aspire to advantages which the Constitution denies them, merely to know and appreciate those which it guarantees them . . . Men are destined to live on the stage of the world. A public didactics suits them: it early places before their optics all the scenes of life: but the proportions are different. The paternal domicile is better for the teaching of women; they have less need to acquire to deal with the interests of others, than to acquaint themselves to a at-home and secluded life.

Wollstonecraft dedicated the Rights of Woman to Talleyrand: "Having read with smashing pleasure a pamphlet which you have lately published, I dedicate this book to you; to induce you to reconsider the field of study, and maturely weigh what I accept avant-garde respecting the rights of adult female and national teaching."[6] At the end of 1791, French feminist Olympe de Gouges had published her Proclamation of the Rights of Adult female and of the Female Citizen, and the question of women's rights became primal to political debates in both French republic and Britain.[2]

The Rights of Woman is an extension of Wollstonecraft's arguments in the Rights of Men. In the Rights of Men, as the title suggests, she is concerned with the rights of detail men (18th-century British men) while in the Rights of Woman, she is concerned with the rights afforded to "adult female", an abstract category. She does not isolate her statement to 18th-century women or British women. The first chapter of the Rights of Adult female addresses the outcome of natural rights and asks who has those inalienable rights and on what grounds. She answers that since natural rights are given by God, for one segment of society to deny them to another segment is a sin.[7] The Rights of Woman thus engages not only specific events in France and in Great britain but too larger questions existence raised by political philosophers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[8]

Themes [edit]

The Rights of Woman is a long (virtually 87,000 words) essay that introduces all of its major topics in the opening chapters and and so repeatedly returns to them, each time from a dissimilar signal of view. It also adopts a hybrid tone that combines rational statement with the fervent rhetoric of sensibility. Wollstonecraft did not apply the formal argumentation or logical prose style common to 18th-century philosophical writing.[9]

In the 18th century, sensibility was a concrete phenomenon that came to exist attached to a specific set of moral beliefs. Physicians and anatomists believed that the more sensitive people'south nerves, the more emotionally afflicted they would be past their surroundings. Since women were idea to take keener nerves than men, it was too believed that women were more than emotional than men.[x] The emotional excess associated with sensibility also theoretically produced an ethic of compassion: those with sensibility could easily sympathise with people in pain. Thus historians take credited the discourse of sensibility and those who promoted it with the increased humanitarian efforts, such as the movement to abolish the slave merchandise.[11] But sensibility too paralysed those who had too much of it; equally scholar Chiliad. J. Barker-Benfield explains, "an innate refinement of nerves was as well identifiable with greater suffering, with weakness, and a susceptibility to disorder".[10]

By the time Wollstonecraft was writing the Rights of Woman, sensibility had already been under sustained attack for a number of years.[12] Sensibility, which had initially promised to draw individuals together through sympathy, was now viewed as "profoundly separatist"; novels, plays, and poems that employed the language of sensibility asserted individual rights, sexual freedom, and unconventional familial relationships based only upon feeling.[13] Furthermore, every bit Janet Todd, another scholar of sensibility, argues, "to many in Britain the cult of sensibility seemed to have feminized the nation, given women undue prominence, and emasculated men."[14]

Rational education [edit]

I of Wollstonecraft'due south central arguments in the Rights of Woman is that women should exist educated in a rational manner to requite them the opportunity to contribute to society. In the 18th century, information technology was frequently assumed by both educational philosophers and conduct book writers, who wrote what ane might think of every bit early self-help books,[15] that women were incapable of rational or abstract thought. Women, it was believed, were as well susceptible to sensibility and too frail to be able to think clearly. Wollstonecraft, forth with other female reformers such equally Catharine Macaulay and Hester Chapone, maintained that women were indeed capable of rational thought and deserved to be educated. She argued this signal in her own conduct book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), in her children'due south book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788), as well equally in the Rights of Adult female.[xvi]

Stating in her preface that "my main argument is built on this elementary principle, that if [woman] be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge and virtue; for truth must be common to all", Wollstonecraft contends that lodge will degenerate without educated women, especially because mothers are the principal educators of young children.[17] She attributes the problem of uneducated women to men and "a false system of didactics, gathered from the books written on this subject field by men who [consider] females rather equally women than human creatures".[eighteen] Women are capable of rationality; information technology only appears that they are not, because men have refused to educate them and encouraged them to be frivolous (Wollstonecraft describes silly women as "spaniels" and "toys"[xix]).[20]

Wollstonecraft attacks conduct book writers such equally James Fordyce and John Gregory also every bit educational philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau who argue that a woman does not demand a rational pedagogy. (Rousseau famously argues in Emile [1762] that women should be educated for the pleasure of men; Wollstonecraft, infuriated past this statement, attacks not only it but as well Rousseau himself.[21]) Intent on illustrating the limitations that contemporary educational theory placed upon women, Wollstonecraft writes, "taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the listen shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its aureate cage, simply seeks to adorn its prison",[22] implying that without this damaging ideology, which encourages young women to focus their attention on dazzler and outward accomplishments, they could achieve much more than. Wives could be the rational "companions" of their husbands and even pursue careers should they so cull: "women might certainly study the art of healing, and exist physicians likewise as nurses. And midwifery, decency seems to allot to them . . . they might, likewise, written report politics . . . Business concern of various kinds, they might too pursue."[23]

For Wollstonecraft, "the near perfect education" is "an do of the understanding as is all-time calculated to strengthen the trunk and form the middle. Or, in other words, to enable the individual to attach such habits of virtue as will render it contained."[24] In add-on to her wide philosophical arguments, Wollstonecraft lays out a specific plan for national teaching to counter Talleyrand'south. In Affiliate 12, "On National Education", she proposes that children be sent to gratis twenty-four hours schools too as given some education at home "to inspire a dearest of home and domestic pleasures". She likewise maintains that schooling should be co-educational, contending that men and women, whose marriages are "the cement of lodge", should exist "educated afterward the aforementioned model."[25]

Feminism [edit]

The Debutante (1807) by Henry Fuseli; "Woman, the victim of male social conventions, is tied to the wall, made to run up and guarded past governesses. The picture reflects Mary Wollstonecraft's views in The Rights of Women [sic]".[26]

It is debatable to what extent the Rights of Adult female is a feminist text; considering the definitions of feminist vary, unlike scholars take come up to different conclusions. Wollstonecraft would never have referred to her text as feminist because the words feminist and feminism were not coined until the 1890s.[27] Moreover, there was no feminist motility to speak of during Wollstonecraft's lifetime. Still, Rights of Woman is often considered "the ur-document of mod liberal feminism."[28] In the introduction to her foundational piece of work on Wollstonecraft'south thought, Barbara Taylor writes:[29]

Describing [Wollstonecraft's philosophy] as feminist is problematic, and I practise it only after much consideration. The label is of grade anachronistic . . . Treating Wollstonecraft's thought as an anticipation of nineteenth and twentieth-century feminist statement has meant sacrificing or distorting some of its key elements. Leading examples of this . . . have been the widespread neglect of her religious behavior, and the misrepresentation of her as a conservative liberal, which together have resulted in the deportation of a religiously inspired utopian radicalism by a secular, class-partisan reformism as alien to Wollstonecraft's political project as her dream of a divinely promised age of universal happiness is to our own. Even more of import however has been the imposition on Wollstonecraft of a heroic-individualist brand of politics utterly at odds with her own ethically driven case for women'due south emancipation. Wollstonecraft'southward leading ambition for women was that they should attain virtue, and it was to this end that she sought their liberation.

In the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft does not make the claim for gender equality using the same arguments or the same linguistic communication that late 19th- and 20th century feminists later would. For instance, rather than unequivocally stating that men and women are equal, Wollstonecraft contends that men and women are equal in the eyes of God, which means that they are both subject field to the aforementioned moral police.[30] For Wollstonecraft, men and women are equal in the most important areas of life. While such an thought may not seem revolutionary to 21st-century readers, its implications were revolutionary during the 18th century. For case, information technology implied that both men and women—non just women—should exist pocket-sized[31] and respect the sanctity of spousal relationship.[32] Wollstonecraft's argument exposed the sexual double standard of the late 18th century and demanded that men adhere to the same virtues demanded of women.[33]

Nevertheless, Wollstonecraft'due south arguments for equality stand in contrast to her statements respecting the superiority of masculine strength and valour.[34] Wollstonecraft famously and ambiguously states:[35]

Let it not be ended, that I wish to invert the order of things; I have already granted, that, from the constitution of their bodies, men seem to exist designed by Providence to reach a greater degree of virtue. I speak collectively of the whole sex activity; but I see not the shadow of a reason to conclude that their virtues should differ in respect to their nature. In fact, how tin can they, if virtue has only one eternal standard? I must therefore, if I reason consequentially, as strenuously maintain that they take the same simple direction, as that there is a God.

Moreover, Wollstonecraft calls on men, rather than women, to initiate the social and political changes she outlines in the Rights of Woman. Considering women are uneducated, they cannot alter their own situation—men must come up to their help.[36] Wollstonecraft writes at the finish of her chapter "Of the Pernicious Effects Which Arise from the Unnatural Distinctions Established in Club":[37]

I and so would fain convince reasonable men of the importance of some of my remarks; and prevail on them to counterbalance dispassionately the whole tenor of my observations. – I entreatment to their understandings; and, every bit a fellow-creature, claim, in the name of my sexual practice, some interest in their hearts. I entreat them to assistance to emancipate their companion, to make her a assist meet for them! Would men but generously snap our chains, and be content with rational fellowship instead of slavish obedience, they would find us more observant daughters, more affectionate sisters, more than true-blue wives, more reasonable mothers – in a word, ameliorate citizens.

It is Wollstonecraft's terminal novel, Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798), the fictionalized sequel to the Rights of Woman, that is usually considered her virtually radical feminist work.[38]

Sensibility [edit]

I of Wollstonecraft'due south most scathing criticisms in the Rights of Woman is against faux and excessive sensibility, particularly in women. She argues that women who succumb to sensibility are "diddled about by every momentary gust of feeling"; because these women are "the prey of their senses", they cannot recollect rationally.[39] In fact, not only practise they do damage to themselves just they also exercise harm to all of culture: these are not women who can refine civilization – these are women who will destroy it. But reason and feeling are not independent for Wollstonecraft; rather, she believes that they should inform each other. For Wollstonecraft the passions underpin all reason.[40] This was a theme that she would return to throughout her career, but particularly in her novels Mary: A Fiction (1788) and Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman. For the 18th-century Scottish philosopher David Hume reason is dominated by the passions. He held that passions rather than reason govern homo behaviour, famously proclaiming in A Treatise of Man Nature that "Reason is, and ought only to exist the slave of the passions."[41]

As part of her argument that women should not exist overly influenced by their feelings and emotions, Wollstonecraft emphasises that they should non exist constrained by or made slaves to their bodies or their sexual feelings.[42] This particular statement has led many modern feminists to propose that Wollstonecraft intentionally avoids granting women any sexual want. Cora Kaplan argues that the "negative and prescriptive assault on female sexuality" is a "leitmotif" of the Rights of Woman.[43] For example, Wollstonecraft advises her readers to "calmly permit passion subside into friendship" in the platonic companionate marriage (that is, in the platonic of a love-based marriage that was developing at the time).[44] It would be better, she writes, when "two virtuous young people marry . . . if some circumstances checked their passion".[45] Co-ordinate to Wollstonecraft, "honey and friendship cannot subsist in the same bosom".[45] Every bit Mary Poovey explains, "Wollstonecraft betrays her fear that female want might in fact court human being's lascivious and degrading attentions, that the subordinate position women have been given might even be deserved. Until women can transcend their fleshly desires and fleshly forms, they will exist hostage to the body."[46] If women are non interested in sexuality, they cannot exist dominated by men. Wollstonecraft worries that women are consumed with "romantic wavering", that is, they are interested only in satisfying their lusts.[47] Because the Rights of Adult female eliminates sexuality from a adult female's life, Kaplan contends, it "expresses a violent antagonism to the sexual" while at the same time "exaggerat[ing] the importance of the sensual in the everyday life of women". Wollstonecraft was so determined to wipe sexuality from her picture of the platonic adult female that she concluded up foregrounding information technology by insisting upon its absence.[48] But as Kaplan and others have remarked, Wollstonecraft may take been forced to make this sacrifice: "it is important to remember that the notion of woman every bit politically enabled and independent [was] fatally linked [during the eighteenth century] to the unrestrained and roughshod practise of her sexuality."[49]

Republicanism [edit]

Claudia Johnson, a prominent Wollstonecraft scholar, has chosen the Rights of Adult female "a republican manifesto".[50] Johnson contends that Wollstonecraft is hearkening back to the Republic tradition of the 17th century and attempting to reestablish a republican ethos. In Wollstonecraft's version, there would exist stiff, merely separate, masculine and feminine roles for citizens.[51] Co-ordinate to Johnson, Wollstonecraft "denounces the collapse of proper sexual distinction as the leading feature of her age, and as the grievous consequence of sentimentality itself. The problem undermining society in her view is feminized men".[52] If men feel costless to adopt both the masculine position and the sentimental feminine position, she argues, women have no position open to them in society.[53] Johnson therefore sees Wollstonecraft equally a critic, in both the Rights of Men and the Rights of Woman, of the "masculinization of sensitivity" in such works as Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France.[54]

In the Rights of Woman Wollstonecraft adheres to a version of republicanism that includes a conventionalities in the eventual overthrow of all titles, including the monarchy. She also briefly suggests that all men and women should exist represented in government. But the bulk of her "political criticism", as Chris Jones, a Wollstonecraft scholar, explains, "is couched predominantly in terms of morality".[55] Her definition of virtue focuses on the individual's happiness rather than, for example, the good of the entire gild.[55] This is reflected in her explanation of natural rights. Because rights ultimately proceed from God, Wollstonecraft maintains that in that location are duties, tied to those rights, incumbent upon each and every person. For Wollstonecraft, the individual is taught republicanism and benevolence inside the family; domestic relations and familial ties are crucial to her understanding of social cohesion and patriotism.[56]

Grade [edit]

In many ways the Rights of Adult female is inflected past a bourgeois view of the globe, as is its direct predecessor the Rights of Men. Wollstonecraft addresses her text to the middle grade, which she calls the "near natural land". She also frequently praises modesty and manufacture, virtues which, at the time, were associated with the heart form.[57] From her position as a middle-course writer arguing for a heart-grade ethos, Wollstonecraft also attacks the wealthy, criticizing them using the same arguments she employs confronting women. She points out the "false-refinement, immorality, and vanity" of the rich, calling them "weak, bogus beings, raised above the mutual wants and affections of their race, in a premature unnatural style [who] undermine the very foundation of virtue, and spread corruption through the whole mass of guild".[58]

Simply Wollstonecraft's criticisms of the wealthy exercise not necessarily reflect a concomitant sympathy for the poor. For her, the poor are fortunate because they volition never be trapped by the snares of wealth: "Happy is it when people take the cares of life to struggle with; for these struggles prevent their becoming a casualty to enervating vices, merely from idleness!"[59] Moreover, she contends that clemency has only negative consequences because, as Jones puts it, she "sees it as sustaining an unequal club while giving the appearance of virtue to the rich".[60]

In her national plan for education, she retains class distinctions (with an exception for the intelligent), suggesting that: "Later the age of nine, girls and boys, intended for domestic employments, or mechanical trades, ought to be removed to other schools, and receive instruction, in some measure appropriated to the destination of each individual ... The young people of superior abilities, or fortune, might now be taught, in another school, the dead and living languages, the elements of science, and continue the study of history and politics, on a more than extensive scale, which would not exclude polite literature."[61]

Rhetoric and manner [edit]

In attempting to navigate the cultural expectations of female person writers and the generic conventions of political and philosophical discourse, Wollstonecraft, as she does throughout her oeuvre, constructs a unique blend of masculine and feminine styles in the Rights of Woman.[62] She uses the linguistic communication of philosophy, referring to her piece of work equally a "treatise" with "arguments" and "principles".[62] Nevertheless, Wollstonecraft also uses a personal tone, employing "I" and "you", dashes and exclamation marks, and autobiographical references to create a distinctly feminine voice in the text.[9] The Rights of Woman farther hybridizes its genre by weaving together elements of the behave book, the curt essay, and the novel, genres oft associated with women, while at the same time claiming that these genres could be used to discuss philosophical topics such every bit rights.[63]

Although Wollstonecraft argues against excessive sensibility, the rhetoric of the Rights of Woman is at times heated and attempts to provoke the reader.[64] Many of the about emotional comments in the volume are directed at Rousseau. For example, after excerpting a long passage from Emile (1762), Wollstonecraft pithily states, "I shall make no other comments on this ingenious passage, than just to notice, that it is the philosophy of lasciviousness."[65] A mere folio later, after indicting Rousseau'due south program for female person education, she writes "I must relieve myself by drawing some other moving picture."[66] These terse exclamations are meant to draw the reader to her side of the argument (it is assumed that the reader will concur with them). While she claims to write in a plain style so that her ideas will reach the broadest possible audience,[67] she really combines the plain, rational language of the political treatise with the poetic, passionate language of sensibility to demonstrate that i tin can combine rationality and sensibility in the aforementioned cocky.[68]

In her efforts to vividly draw the condition of women within society, Wollstonecraft employs several different analogies.[69] She often compares women to slaves, arguing that their ignorance and powerlessness places them in that position. Simply at the same time, she also compares them to "capricious tyrants" who use cunning and deceit to dispense the men around them. At one bespeak, she reasons that a woman can become either a slave or tyrant, which she describes as two sides of the same money.[70] Wollstonecraft also compares women to soldiers; like military men, they are valued just for their advent and obedience. And like the rich, women'southward "softness" has "debased flesh".[71]

Revision [edit]

Wollstonecraft was forced to write the Rights of Woman hurriedly to respond to Talleyrand and ongoing events. Upon completing the work, she wrote to her friend William Roscoe: "I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the discipline. – Do not suspect me of imitation modesty – I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could take written a better volume, in every sense of the discussion . . . I intend to finish the adjacent volume before I brainstorm to impress, for it is non pleasant to have the Devil coming for the conclusion of a canvas fore it is written."[72] When Wollstonecraft revised the Rights of Woman for the second edition, she took the opportunity non only to set up small spelling and grammer mistakes but also to bolster the feminist claims of her argument.[73] She inverse some of her statements regarding female person and male departure to reverberate a greater equality between the sexes.[74]

Wollstonecraft never wrote the second function to the Rights of Woman, although William Godwin published her "Hints", which were "chiefly designed to accept been incorporated in the second part of the Vindication of the Rights of Woman", in the posthumous collection of her works.[75] Yet, she did brainstorm writing the novel Maria: or, The Wrongs of Adult female, which nearly scholars consider a fictionalized sequel to the Rights of Woman. It was unfinished at her death and also included in the Posthumous Works published past Godwin.[76]

Reception and legacy [edit]

When it was get-go published in 1792, the Rights of Adult female was reviewed favourably by the Analytical Review, the General Magazine, the Literary Magazine, New York Mag, and the Monthly Review, although the assumption persists that Rights of Adult female received hostile reviews.[77] It was near immediately released in a second edition in 1792, several American editions appeared, and it was translated into French. Taylor writes that "it was an immediate success".[78] Moreover, other writers such as Mary Hays and Mary Robinson specifically alluded to Wollstonecraft's text in their ain works. Hays cited the Rights of Woman in her novel Memoirs of Emma Courtney (1796) and modelled her female characters later on Wollstonecraft's ideal woman.[79]

Although female conservatives such as Hannah More than excoriated Wollstonecraft personally, they actually shared many of the same values. As the scholar Anne Mellor has shown, both More and Wollstonecraft wanted a society founded on "Christian virtues of rational benignancy, honesty, personal virtue, the fulfillment of social duty, austerity, sobriety, and hard work".[80] During the early 1790s, many writers inside British club were engaged in an intense debate regarding the position of women in guild. For example, the respected poet and essayist Anna Laetitia Barbauld and Wollstonecraft sparred dorsum and along; Barbauld published several poems responding to Wollstonecraft's piece of work and Wollstonecraft commented on them in footnotes to the Rights of Woman.[81] The work also provoked outright hostility. The bluestocking Elizabeth Carter was unimpressed with the piece of work.[82] Thomas Taylor, the Neoplatonist translator who had been a landlord to the Wollstonecraft family in the tardily 1770s, swiftly wrote a satire called A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes: if women accept rights, why non animals too?[82]

After Wollstonecraft died in 1797, her married man William Godwin published his Memoirs of the Writer of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798). He revealed much virtually her private life that had previously not been known to the public: her illegitimate child, her love affairs, and her attempts at suicide. While Godwin believed he was portraying his married woman with love, sincerity, and compassion, gimmicky readers were shocked past Wollstonecraft's unorthodox lifestyle and she became a reviled figure. Richard Polwhele targeted her in item in his anonymous long poem The Unsex'd Females (1798), a defensive reaction to women's literary self-assertion: Hannah More is Christ to Wollstonecraft's Satan. His poem was "well known" among the responses A Vindication.[83] Most reviewers of the poem considered it artistically uninspiring and tedious, though some conservative publications praised its political stance.[84]

Wollstonecraft's ideas became associated with her life story and women writers felt that it was unsafe to mention her in their texts. Hays, who had previously been a close friend[85] and an outspoken abet for Wollstonecraft and her Rights of Woman, for case, did not include her in the drove of Illustrious and Historic Women she published in 1803.[86] Maria Edgeworth specifically distances herself from Wollstonecraft in her novel Belinda (1802); she caricatures Wollstonecraft as a radical feminist in the grapheme of Harriet Freke.[87] Simply, like Jane Austen, she does non reject Wollstonecraft's ideas. Both Edgeworth and Austen debate that women are crucial to the development of the nation; moreover, they portray women as rational beings who should cull companionate union.[88]

The negative views towards Wollstonecraft persisted for over a century. The Rights of Woman was not reprinted until the middle of the 19th century and information technology nonetheless retained an aura of ill-repute. George Eliot wrote "there is in some quarters a vague prejudice against the Rights of Woman as in some manner or other a reprehensible book, but readers who go to it with this impression volition be surprised to observe it eminently serious, severely moral, and withal rather heavy".[89]

The suffragist (i.e. moderate reformer, as opposed to suffragette) Millicent Garrett Fawcett wrote the introduction to the centenary edition of the Rights of Woman, cleansing the memory of Wollstonecraft and challenge her equally the foremother of the struggle for the vote.[xc] While the Rights of Adult female may have paved the style for feminist arguments, 20th century feminists have tended to utilize Wollstonecraft's life story, rather than her texts, for inspiration;[91] her unorthodox lifestyle convinced them to try new "experiments in living", as Virginia Woolf termed it in her famous essay on Wollstonecraft.[92] All the same, at that place is some prove that the Rights of Woman may be influencing current feminists. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a feminist who is critical of Islam's dictates regarding women, cites the Rights of Woman in her autobiography Infidel, writing that she was "inspired past Mary Wollstonecraft, the pioneering feminist thinker who told women they had the same ability to reason as men did and deserved the aforementioned rights".[93] Miriam Schneir also includes this text in her anthology Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings, labelling it equally i of the essential feminist works.[94] Further testify of the indelible legacy of Wollstonecraft's A Vindication may be seen by direct references in recent historical fiction set up: for example, in The Silk Weaver (1998) set in the late 18th century amid Dublin silk weavers, author Gabrielle Warnock (1998) intervenes every bit narrator to hold up 'Rights of Adult female' for the reader to reverberate upon the politics, morals, and feelings of her female characters.[95] In Death comes to Pemberley (2011)set up in 1803 P.D.James has one male person character reference Rights of Woman in reproving another (Darcy) for denying vocalization to the adult female in matters that business her.[96]

See also [edit]

- Timeline of Mary Wollstonecraft

- A Vindication of the Rights of Men

Notes [edit]

- ^ Sunstein, iii.

- ^ a b Macdonald and Scherf, "Introduction", xi–12.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 43–44.

- ^ Kelly, 107; Sapiro, 26–27.

- ^ Talleyrand, "Rapport sur 50'pedagogy publique", reprinted in Vindications, 394–95.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 101.

- ^ Taylor, 105–6; Kelly, 107.

- ^ Sapiro, 182–84.

- ^ a b Kelly, 110.

- ^ a b Barker-Benfield, 9.

- ^ Barker-Benfield, 224.

- ^ Todd, Sensibility, 144.

- ^ Todd, Sensibility, 136.

- ^ Todd, Sensibility, 133.

- ^ Batchelor, Jennie. "Conduct Volume." The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 169ff; Kelly, 123; Taylor, 14–xv; Sapiro, 27–28; 243–44.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 102; Sapiro, 154–55.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 109.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 144.

- ^ Kelly, 124–26; Taylor, 234–37; Sapiro, 129–30.

- ^ Kelly, 126; Taylor, 14–15; Sapiro, 130–31.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 157.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 286; come across too Kelly, 125–24; Taylor, 14–15.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 129.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, Chapter 12; encounter as well, Kelly, 124–25; 133–34; Sapiro, 237ff.

- ^ Tomory, Peter. The Life and Fine art of Henry Fuseli. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972; p. 217. LCCN 72-77546.

- ^ Feminist and feminism. Oxford English language Dictionary. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ DeLucia, n. pag.

- ^ Taylor, 12; meet too, 55–57; see also Sapiro, 257–59.

- ^ See, for example, Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 126, 146; Taylor, 105–106; 118–twenty.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 102 and 252.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 274.

- ^ DeLucia, n. pag.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 110; Sapiro, 120–21.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 135.

- ^ Poovey, 79; Kelly, 135.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 288.

- ^ Taylor, Chapter 9; Sapiro, 37; 149; 266.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 177.

- ^ Jones, 46.

- ^ Hume, 415.

- ^ See, for example, Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 259–60; Taylor, 116–17.

- ^ Kaplan, "Wild Nights", 35.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 249.

- ^ a b Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 192.

- ^ Poovey, 76.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 194.

- ^ Kaplan, "Wild Nights", 41.

- ^ Kaplan, "Wild Nights", 33; see also Taylor, 118–xix; Taylor, 138ff.

- ^ Johnson, 24.

- ^ Johnson, 29; see also Taylor, 211–22; Sapiro, 82–83.

- ^ Johnson, 23.

- ^ Johnson, 45.

- ^ Johnson, 30.

- ^ a b Jones, 43.

- ^ Jones, 46; Taylor, 211–22; Vindications, 101–102, for example.

- ^ Kelly, 128ff; Taylor, 167–68; Sapiro, 27.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 111; meet also Taylor, 159–61; Sapiro, 91–92.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 169.

- ^ Jones, 45; meet also Taylor, 218–19; Sapiro, 91–92.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 311; Kelly, 132–33.

- ^ a b Kelly, 109.

- ^ Kelly, 113–14; Taylor, 51–53.

- ^ Taylor, Barbara (2004). "Feminists Versus Gallants: Manners and Morals in Enlightenment Great britain" (PDF). Representations. 87: 139–141. doi:10.1525/rep.2004.87.1.125 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 162.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 163.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 111–12.

- ^ Kelly, 109ff; Sapiro, 207–208.

- ^ Kelly, 118ff; Sapiro, 222.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 158; Sapiro, 126.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 165; Taylor, 159–61; Sapiro, 124–26.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd. New York: Penguin Books (2003), 193–94.

- ^ Macdonald and Scherf, "Introduction", 23 and Mellor, 141–42.

- ^ Mellor, 141–42.

- ^ Macdonald and Scherf, Appendix C.

- ^ Sapiro, 30–31.

- ^ Janes, 293; Sapiro, 28–29.

- ^ Taylor, 25; see also, Janes, 293–302; Wardle, 157–58; Kelly, 135–36; Sapiro 28–29.

- ^ Mellor, 143–44 and 146.

- ^ Mellor, 147.

- ^ Mellor, 153.

- ^ a b Gordon, 154

- ^ Adriana Craciun, Mary Wollstonecraft'due south a Vindication of the Rights of Woman: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2002, 2).

- ^ "Introduction". The Unsex'd Females. Academy of Virginia Electronic Texts Center. 1994. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Pennell, Elizabeth Robins p351, Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1884).

- ^ Mellor, 145; Taylor, 27–28.

- ^ Mellor, 155; Taylor, 30–31.

- ^ Mellor, 156.

- ^ Quoted in Sapiro, 30.

- ^ Gordon, 521

- ^ Kaplan,"Mary Wollstonecraft's reception and legacies".

- ^ Woolf, Virginia. "The Four Figures Archived iii April 2007 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 17 Feb 2007.

- ^ Hirsi Ali, Ayaan. Infidel. New York: Gratis Press (2007), 295.

- ^ Schneir, Miriam (1972). Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings. Vintage Books.

- ^ Warnock, Gabrielle (1998). The Silk Weaver. Galway: Trident Printing Ltd. p. 160. ISBN1900724197.

- ^ James, P.D. (2011). Death comes to Pemberley. Faber and Faber. p. 134. ISBN9780571283583.

Bibliography [edit]

Modern reprints [edit]

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Complete Works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd and Marilyn Butler. 7 vols. London: William Pickering, 1989. ISBN 0-8147-9225-i.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Vindications: The Rights of Men and The Rights of Woman. Eds. D.Fifty. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf. Toronto: Broadview Literary Texts, 1997. ISBN 1-55111-088-1

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Ed. Miriam Brody Kramnick. Rev. ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2004. ISBN 0-14-144125-ix.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Ed. Deidre Shauna Lynch. 3rd ed. New York: W. Due west. Norton and Company, 2009. ISBN 0-393-92974-4.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Men and A Vindication of the Rights of Adult female. Ed. Sylvana Tomaselli. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Printing, 1995. ISBN 0-521-43633-8.

Contemporary reviews [edit]

- Belittling Review 12 (1792): 241–249; 13 (1792): 418–489.

- Christian Miscellany i (1792): 209–212.

- Disquisitional Review New Serial 4 (1792): 389–398; 5 (1792): 132–141.

- General Magazine and Imperial Review 6.2 (1792): 187–191.

- Literary Magazine and British Review 8 (1792); 133–139.

- Monthly Review New Series 8 (1792): 198–209.

- New Almanac Annals 13 (1792): 298.

- New-York Magazine 4 (1793): 77–81.

- Scots Magazine 54 (1792): 284–290.

- Sentimental and Masonic Magazine 1 (1792): 63–72.

- Boondocks and State Magazine 24 (1792): 279.

Secondary sources [edit]

- Barker-Benfield, G.J. The Civilization of Sensibility: Sex activity and Society in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. ISBN 0-226-03714-two.

- DeLucia, JoEllen. "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman". The Literary Encyclopedia, Volume i.2.1.06: English Writing and Civilization of the Romantic Catamenia, 1789-1837, 2011.

- Gordon, Lyndall. Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. Great Britain: Virago, 2005. ISBN 1-84408-141-9.

- Hume, David. A Treatise of Man Nature 1. London: John Noon, 1739. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Janes, R.M. "On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft'southward A Vindication of the Rights of Woman". Journal of the History of Ideas 39 (1978): 293–302.

- Johnson, Claudia L. Equivocal Beings: Politics, Gender, and Sentimentality in the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0-226-40184-7.

- Jones, Chris. "Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindications and their political tradition". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia Fifty. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-4.

- Kaplan, Cora. "Mary Wollstonecraft's reception and legacies". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-four.

- Kaplan, Cora. "Pandora's Box: Subjectivity, Class and Sexuality in Socialist Feminist Criticism". Sea Changes: Essays on Culture and Feminism. London: Verso, 1986. ISBN 0-86091-151-nine.

- Kaplan, Cora. "Wild Nights: Pleasure/Sexuality/Feminism". Bounding main Changes: Essays on Civilisation and Feminism. London: Verso, 1986. ISBN 0-86091-151-9.

- Kelly, Gary. Revolutionary Feminism: The Mind and Career of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: St. Martin's, 1992. ISBN 0-312-12904-1.

- Mellor, Anne K. "Mary Wollstonecraft'due south A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and the women writers of her day". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing, 2002. ISBN 0-521-78952-4.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology equally Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 1984. ISBN 0-226-67528-9.

- Sapiro, Virginia. A Vindication of Political Virtue: The Political Theory of Mary Wollstonecraft. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. ISBN 0-226-73491-ix.

- Sunstein, Emily W. A Different Face up: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York: Harper and Row, 1975. ISBN 0-06-014201-iv.

- Taylor, Barbara. Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing, 2003. ISBN 0-521-66144-7.

- Todd, Janet. Sensibility: An introduction. London: Methuen, 1986. ISBN 0-416-37720-three.

- Wardle, Ralph M. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Disquisitional Biography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1951.

External links [edit]

- 1796 edition of Rights of Woman

- Rights of Woman at Projection Gutenberg

-

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Mary Wollstonecraft: A 'Speculative and Dissenting Spirit' by Janet Todd at www.bbc.co.u.k.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects From the Collections at the Library of Congress

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Vindication_of_the_Rights_of_Woman

Belum ada Komentar untuk "what did Wollstonecraft argue that men must do if they want to prove women are inferior"

Posting Komentar